“Fiscal dominance” refers to the state’s expenditures (fiscal policy) dominating monetary policy. Instead of the legislature (Congress in the US) controlling government expenditures while the central bank (the Fed) tries to control inflation, the latter helps finance expenditures and Congress obtains more leeway to run deficits. Fiscal dominance is the opposite of central bank independence. The idea is making a comeback (see Ian Smith, “Investors Warn of ‘New Era of Fiscal Dominance’ in Global Markets,” Financial Times, August 20, 2025; see also Greg Ip, “Get Ready for the End of Fed Independence,” Wall Street Journal, August 26, 2025).

From a monetarist viewpoint, fiscal dominance would lead the Fed, under political pressure, to increase the money supply to stimulate the economy, if not to finance the government more directly. Other macroeconomic theories emphasize different means of intervention and causality chains. For example, the central bank may try to push down interest rates in order to reduce the government’s interest costs on its deficits and the rolling of its debt.

As investors start to fear inflation, however, long-term interest rates, including on mortgages, will increase because a higher risk premium is required to incentivize the lenders. This probably explains the recent increase in the spread between long-term and short-term interest rates. (Co-blogger Jon Murphy made important related points earlier this week.)

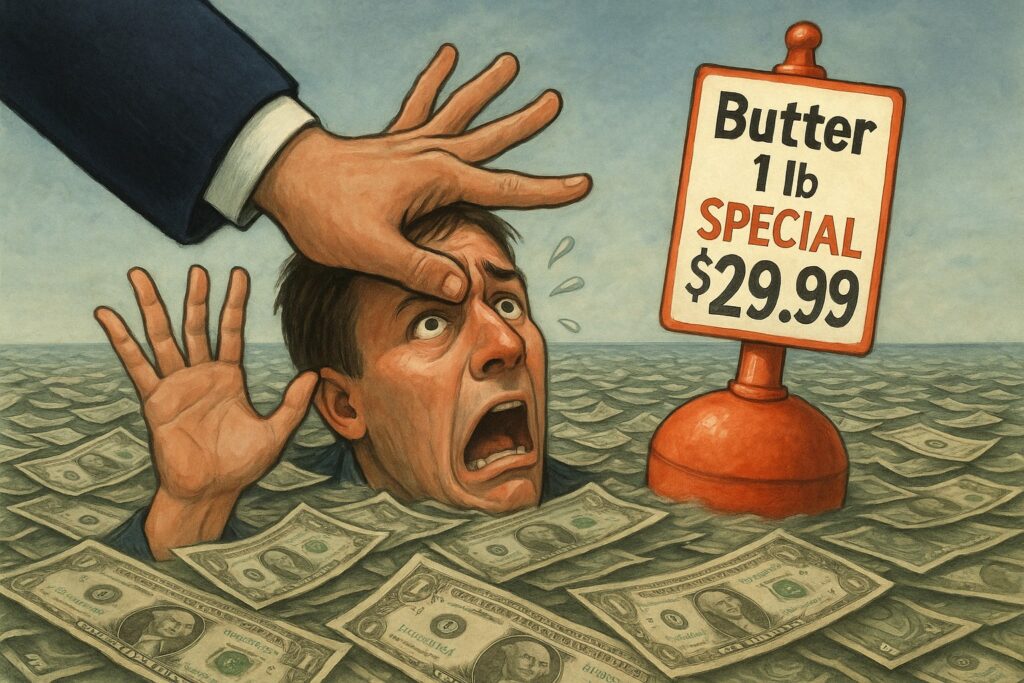

One way or another, sooner or later, fiscal dominance will lead to inflation, which is defined as a sustained increase in the price level. It is sustained in the sense that the central bank sustains it or “accommodates” it. Under fiscal dominance, the central bank cannot resist pressure from the ruling politicians. Many government expenditures, such as Social Security, are indexed to inflation, but some unprotected political clienteles will cry for assistance. Worsening budget deficits and further financing assistance from an obedient central bank can thus generate a self-perpetuating vicious circle.

“Financial repression” is the use of financial and regulatory means by the government to divert resources away from the private economy to itself. Inflation is a major instrument of financial repression. For example, it played a large part in financing WWII as well as the growth of the welfare state in the 1970s. The political pressures for fiscal dominance suggest that financial repression through inflation will return.

In this context, inflation is the result of the government bidding up prices and winning the bidding to get the resources to produce and do what it wants. The government can always win (in the virtual auctions that markets are) if the obedient central bank finances whatever its master needs to be among the highest bidders. Note that the government largely bids against its own citizens.

Populist governments have been habitual practitioners of financial repression through inflation. In their study on the economics of populist regimes over more than a century, many of them South American and European, Cas Mudde (University of Georgia and University of Oslo) and Cristóbal Rovira Kaltwasser (Diego Portales University in Santiago de Chile) provide some econometric evidence to that effect (“Populist Leaders and the Economy,” American Economic Review, vol. 113, no. 12 [2023]). Inflation produces a stealth increase in real taxation (gaining control over real resources), which allows the government to bribe the clienteles whose support is most needed. Think of Nicolás Maduro or Recep Tayyip Erdoğan. The latter also believed that pushing down interest rates would reduce inflation, with the consequence that the annual increase in the country’s consumer price index reached 80% and is still half that rate (“Turkey’s Economic Woes Catch Up With Erdoğan,” Financial Times, June 27, 2025).

After the speech of the Fed’s chairman in Jackson Hole, an editorial in the Wall Street Journal notes (“Powell Flips the Fed’s ‘Framework,’” August 22, 2025):

The Fed Chair on Friday seemed to move toward the view that tariffs won’t lead to permanently higher inflation. “A reasonable base case is that the effects will be relatively short lived—a one-time shift in the price level,” Mr. Powell said.

The editorialists could have been a bit more explicit on this point. A supply shock caused by a large increase in tariffs shifts the production possibility frontier downward and thus generates a one-time increase in the general price level. It may not cause inflation in the sense of a sustained increase in the price level, but only if the Fed doesn’t sustain it by increasing the money supply or helping finance the government deficit in some way (see my “Assessing Trump’s New Tariff Ideas,” Regulation, vol. 47, no. 3 [Fall 2024]).

These rather basic observations do not imply that a more radical criticism of central banking is not warranted (see my post “A Bad Solution to Very Real Problems,” January 31, 2018). On the contrary, the Fed participates in the logic of self-sustaining government intervention. Government intervention begets government intervention. At a time when nationalization appears (again!) as the solution to all problems, radical critiques need to be emphasized.

******************************

Financial repression, by ChatGPT