The National Institutes of Health (NIH) has launched a groundbreaking five-year consortium aimed at addressing the alarming stillbirth rates in the United States, which it has described as “unacceptably high.” This initiative, funded at $37 million, represents a significant commitment from the agency to tackle the tragic loss of life experienced by families when a child is stillborn at 20 weeks gestation or later.

The announcement, made last week, has been met with enthusiasm from healthcare professionals, researchers, and families alike, who have long sought more attention and resources dedicated to combating stillbirth. “What we’re really excited about is not only the investment in trying to prevent stillbirth but also continuing that work with the community to guide the research,” said Alison Cernich, acting director of the NIH’s Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.

The consortium will bring together four clinical sites and a data coordinating center from across the country, including California, Oregon, Utah, New York, and North Carolina. Each site will leverage its unique expertise to focus on predicting and preventing stillbirths while also addressing the essential aspects of bereavement and mental health support for families who experience this devastating loss. Research suggests that out of the more than 20,000 stillbirths that occur annually in the U.S., as many as 25% may be preventable, with that number increasing to nearly 50% for deliveries at 37 weeks or more.

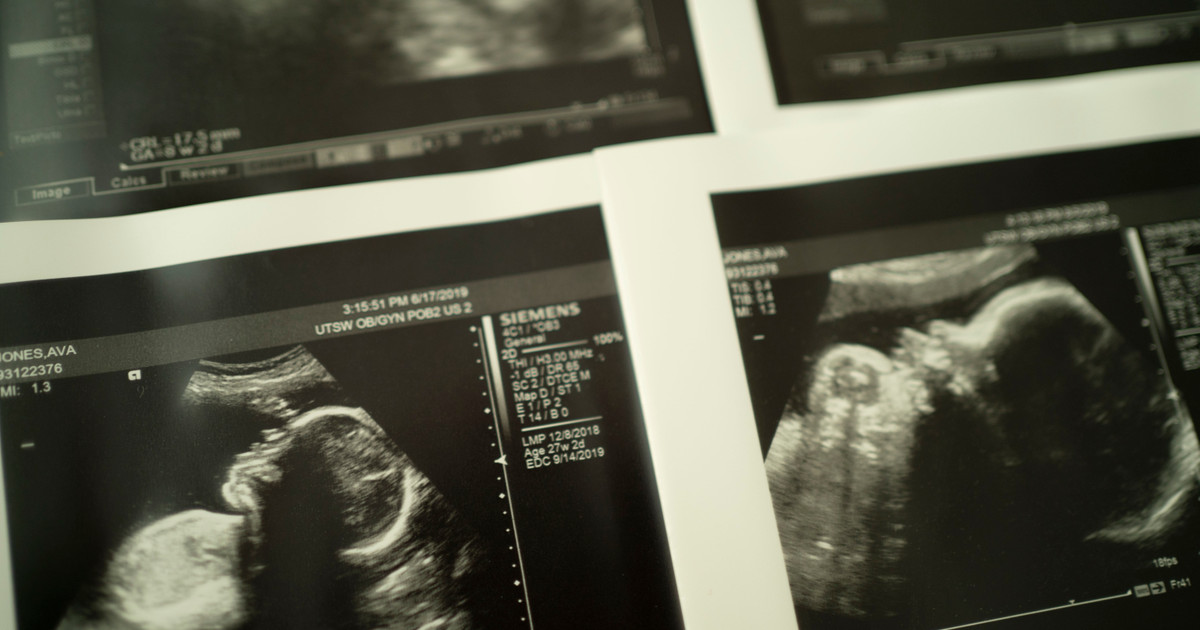

As the teams prepare to convene for their inaugural meeting, they are set to explore various research targets. These include understanding the reasons behind placental failure and poor fetal growth, assessing signs of decreased fetal movement, determining optimal delivery timing, and employing advanced technologies like blood tests, biomarkers, and ultrasounds to better predict stillbirth risks. Additionally, the consortium may investigate how electronic medical records and artificial intelligence can aid healthcare providers in identifying early warning signs of stillbirth.

While the initial announcement did not explicitly address racial disparities in stillbirth rates, representatives from the consortium have indicated that they aim to identify factors contributing to heightened risks for certain populations.

For countless families, the aftermath of stillbirth is characterized by a lack of clarity regarding the causes of their loss. The consortium will collaborate closely with the stillbirth community through advisory groups to ensure that their experiences and insights inform the research. The team based in North Carolina is tasked with overseeing data collection and standardization, as incomplete and often inaccurate stillbirth data has hindered previous prevention efforts.

Dr. Cynthia Gyamfi-Bannerman, chair and professor of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive sciences at the University of California, San Diego, who will co-lead the effort there, emphasized the urgency of this initiative. “If we could see the signs and deliver the baby earlier, so that the mom has a live baby, that’s what we’re all hoping for,” she stated.

This consortium marks a significant shift in the national dialogue surrounding stillbirth, a subject that has historically been overlooked in public health discussions. ProPublica has been at the forefront of reporting on stillbirths since 2022, including the release of a documentary in 2025 that followed the journeys of three women striving to improve pregnancy safety in the wake of their own stillbirths.

Debbie Haine Vijayvergiya, one of the individuals featured in the documentary, has tirelessly advocated for Congressional support of stillbirth legislation. Her efforts culminated in the reintroduction of the Stillbirth Health Improvement and Education (SHINE) for Autumn Act, named after her stillborn daughter, just two days after the NIH announced the consortium. “I feel like our moment has finally arrived, and we are being included in all this tremendously important lifesaving work that’s being done,” she expressed.

The NIH’s commitment to addressing stillbirth follows a mandate from Congress to establish a working group focused on the issue, which began in 2022. This group gathered insights directly from stillbirth families and produced a federal report that highlighted the U.S. stillbirth rate as “unacceptably high.” Compared to other wealthy nations, the U.S. significantly lags behind in reducing stillbirth rates.

Dr. Bob Silver, a leading stillbirth expert at the University of Utah Health, has devoted decades to stillbirth prevention and will co-direct the consortium’s efforts in his state. “There’s no question that the ProPublica reporting was intimately tied to this,” he remarked, noting the impact of increased public awareness on the initiative.

While previous studies, such as the NIH’s Human Placenta Project, have indirectly contributed to stillbirth research, this consortium represents the first comprehensive initiative of its kind since the Stillbirth Collaborative Research Network was established over a decade ago. Dr. Uma Reddy, a professor of obstetrics and gynecology at Columbia University, expressed the importance of this new initiative. “We need to be able to get our rates down to similar high-income countries,” she stated. “This initiative to really look at reducing the stillbirth rate and to look at preventing them is so important, and it’s really about time.”

Dr. Karen Gibbins, an assistant professor at Oregon Health & Science University, received the news of her selection for the consortium just after completing her morning clinic. Overwhelmed with emotion, she confirmed the news online before celebrating with her colleagues. “Stillbirth is such a huge public health issue, and one that historically has not received as much attention,” Gibbins remarked. “This investment in centers that will adopt different approaches to combat stillbirth and better care for families who experience it is a piece of hope that I think we all needed.”

The NIH has already allocated the first year of funding, amounting to $7.3 million, which includes $750,000 from the Department of Health and Human Services. Despite recent budget cuts at the NIH, officials remain optimistic about securing funding for the remaining four years of the project. “The reason that we are doing this is because stillbirth affects 1 in 160 deliveries in the United States each year, and it is really traumatic for families, and it is not talked about,” Cernich concluded. “We are in a great place to really try to tackle this preventable tragedy.”