Violet Newborn was settling into a new home on the edge of Midtown and Frasier when her six-month-old son, Logan, began regressing in his developmental milestones. What started as a joyful exploration of the world quickly turned into lethargy; Logan became constipated, lost his appetite, and showed little interest in interacting with others. At daycare, he sat silently, and when his mother pushed him on the swings, he hung his head.

Concerned, Newborn took Logan to the doctor, where blood tests revealed alarming results: his blood lead levels were 16 micrograms per deciliter—well above the acceptable reference value of 3.5 micrograms. This exposure led to developmental delays, behavioral issues, and a loss of communication skills. “He would act out violently—biting me, hitting me, just banging his head on the floor,” she recounted.

The source of Logan’s lead exposure? The very walls of their rental house, where peeling paint—sweet to the taste—had drawn his attention. Newborn, a new mother in the midst of a pandemic, faced the harrowing reality of being unable to afford to move. “It was horrible, absolutely horrible,” she said. “I felt alone, and it was just a very dark time.”

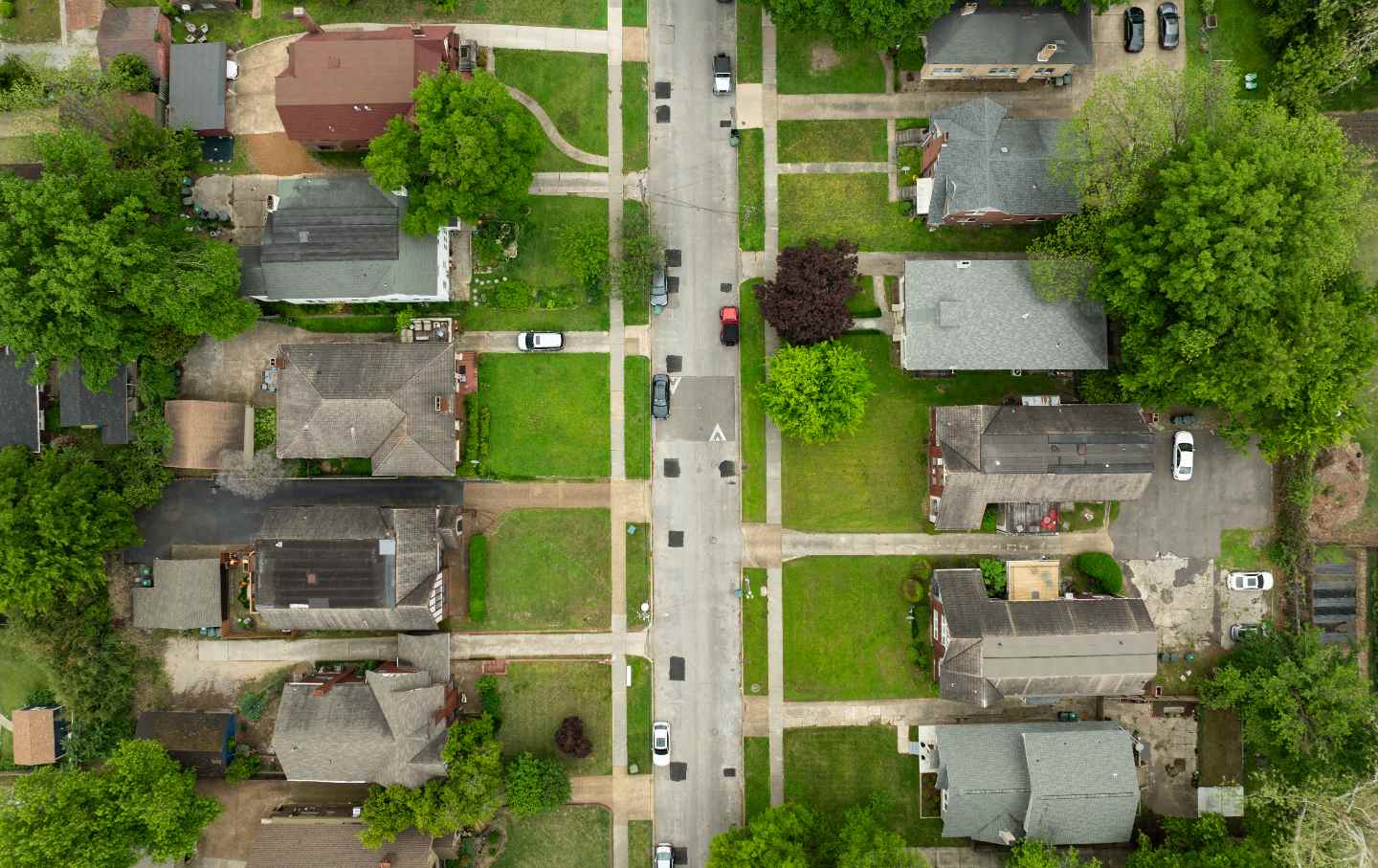

The crisis of lead poisoning is particularly acute in Memphis, where aging infrastructure and housing continue to expose children to this toxic substance. A study from the University of Memphis conducted in 2016 found a direct correlation between lead poisoning hotspots and neighborhoods with the oldest homes, highest child poverty rates, lowest median incomes, and significant populations of Black children.

Despite a federal ban on lead in plumbing and paint over thirty years ago, lead poisoning remains a grim reality for an estimated 500,000 children across the United States each year. The water crisis in Flint, Michigan, which came to light in 2015, serves as a stark reminder of systemic failures in protecting vulnerable communities. A recent study in Chicago revealed that 68 percent of children under six had been exposed to lead in their drinking water, with the impact disproportionately affecting Black and Hispanic neighborhoods.

In South Memphis, the threat of lead poisoning is compounded by environmental hazards. Elon Musk’s company, xAI, has been at odds with environmental advocates over air pollution from its operations, but the struggles for safe living conditions have persisted for decades. A study in 2013 highlighted that air pollution in Southwest Memphis from nearby industrial plants exposed residents to carcinogens, quadrupling the cancer risk compared to the national average.

“If you’ve been exposed repeatedly, it accumulates in your bones and can be released into your bloodstream during times of stress,” explained Debra Bartelli, a research associate professor of urban health at the University of Memphis. “You carry that burden with you for life.”

While lead exposure violates the International Property Maintenance Code, enforcement in Tennessee is weak. According to Sharon Hyde, the Tennessee housing program manager for the nonprofit Green and Healthy Homes, there are no rental ordinances mandating lead inspections. Attempts to establish a mandatory rental registry have been blocked by state lawmakers, influenced by a powerful landlord lobby. “Everything is complaint-based, and many renters are afraid to voice any concerns about their landlords,” Hyde said.

The lack of lead screening for children under six further exacerbates the problem. Pediatricians often do not take the initiative to test for lead, and funding for lead testing and response programs has been inadequate. In 2024, Shelby County screened just 15 percent of its children under six, with 238 found to have elevated blood lead levels.

Compounding these challenges, the lead response programs run by the EPA and CDC have faced significant setbacks. Under the previous administration, staff cuts eliminated vital programs, leaving cities like Milwaukee in a lurch during lead crises. Fortunately, recent legal actions have restored some funding, but the fight against lead exposure continues to be fraught with obstacles.

As Memphis grapples with rising crime rates, federal officials have focused on policing rather than addressing the root causes of community health crises. FBI Director Kash Patel referred to Memphis as the “homicide capital of America,” announcing plans to deploy federal resources to combat crime. In response, State Representative Justin Pearson criticized this approach, advocating instead for investments in community-based safety measures and resources to tackle underlying issues.

Local leaders have largely ignored the health risks posed by lead exposure. In 2022, Anita Tate of the Shelby County Lead Hazard Control Program reached out to the Memphis Shelby County Crime Commission, providing research on lead poisoning, but received no follow-up. Tate manages lead inspection and mitigation efforts in an area where 80 to 90 percent of homes were built before 1978, illustrating the urgent need for action.

Long-term exposure to lead can create an irreversible “body burden,” damaging various internal systems and impairing cognitive abilities. Chet Kibble, an environmental supervisor and lead activist, witnessed firsthand the impact of lead exposure during his tenure at Memphis Light Gas and Water. His concerns about safety led him to resign in 1999, but the consequences of lead contamination persist. Children exposed to lead experience reduced IQs, diminished academic performance, and increased incidences of violent behavior.

Twenty years ago, Kibble discovered lead poisoning in children in the Cooper-Young neighborhood, tracing it back to a lead-painted steel overpass. Although community efforts temporarily mitigated the issue, lead contamination remains pervasive—found in playgrounds, fire hydrants, and residential properties.

Routine testing by the Memphis Shelby County School System recently revealed high lead levels in water sources at 24 local schools, a symptom of the aging infrastructure that continues to fail the community. With many homes and schools built before the ban on lead, the solutions remain costly and often temporary.

Tate noted that their program initially focused on full lead abatements, costing upwards of $30,000 to $50,000 per house, but has since shifted to interim controls averaging $7,000. While these interim measures can temporarily render a home safe, without ongoing maintenance, the risk of lead exposure can return.

Chair of the Shelby County Lead Prevention and Sustainability Commission, LaTricea Adams, expressed concern over the lack of data from the Health Department, which had previously provided testing information by zip code. The absence of this data hampers efforts to advocate for necessary resources and funding to combat lead poisoning effectively.

Newborn’s home was eventually remediated, allowing her son to recover from chronic fatigue. Logan is now six years old, diagnosed with autism—a condition frequently associated with lead exposure—and has developed healthier communication skills. Yet, Newborn remains acutely aware of the plight of other parents still navigating the murky waters of lead poisoning. “My heart goes out to parents in that in-between time,” she said, reflecting on her own struggles to find help. “Not knowing what to do on a daily basis, from sunup to sundown, while they’re waiting for help.”