About two decades ago, Justice Antonin Scalia went on a duck hunting trip with then-Vice President Dick Cheney. This outing became a point of contention when the Supreme Court was reviewing a case that challenged some of Cheney’s official actions during the Bush administration. A party involved in the case requested Scalia to recuse himself due to his personal relationship with the vice president.

In his opinion denying this request, Scalia argued that expecting justices to withdraw from cases involving friends’ official actions would be “utterly disabling.” He noted that many justices reached the Supreme Court precisely because they were friends with the incumbent president or other senior officials, and cited several past instances of close ties between justices and executive branch members.

While one could critique Scalia’s reasoning against recusal, his opinion accurately reflects the elite culture in Washington, D.C. The pool of individuals who receive high-level presidential appointments is relatively small, especially within the Republican Party. Those who ascend to top government roles, whether justices or agency leaders, often develop close acquaintances with their peers through countless meetings and political maneuvering.

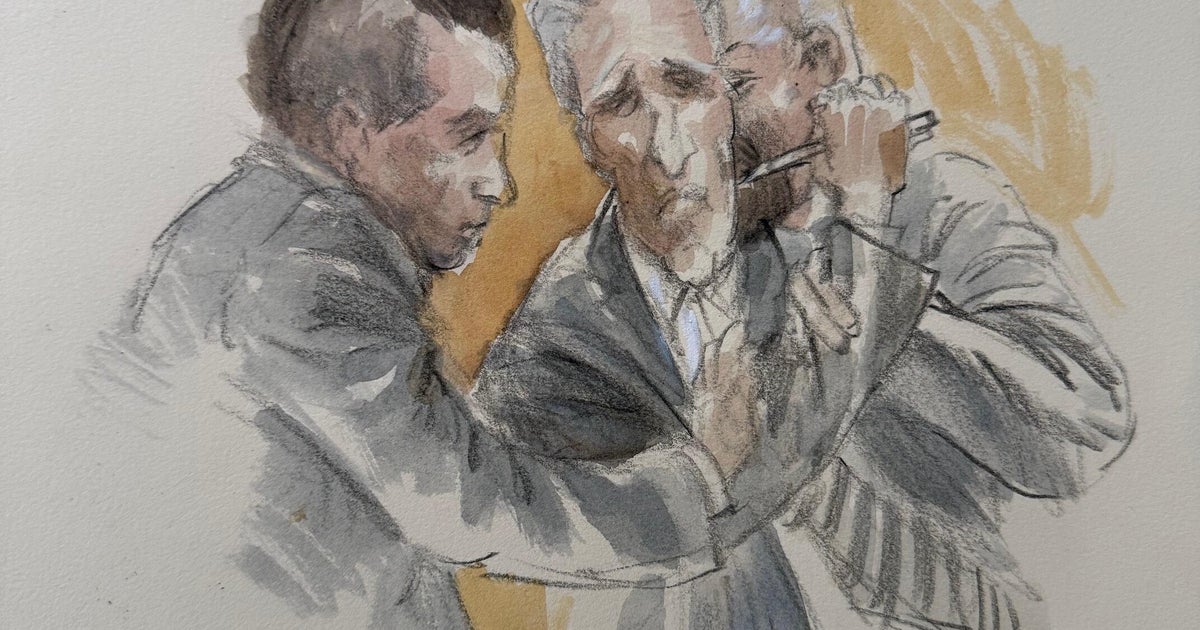

This brings us to Trump’s recent decision to press criminal charges against former FBI Director James Comey—charges so flimsy that Trump had to dismiss a U.S. attorney and replace them with a loyalist to secure the indictment. Although Comey was appointed to lead the FBI by Democratic President Barack Obama, primarily to sidestep a contentious confirmation battle with Senate Republicans, he had identified as a Republican for most of his career. He even announced that he left the party during Trump’s first term. Comey previously held significant positions under Republican President George W. Bush, including serving as deputy attorney general and as the top federal prosecutor in Manhattan.

During his various roles in government, Comey directly collaborated with at least two sitting Supreme Court justices. His time as deputy attorney general coincided with Justice Neil Gorsuch’s tenure in a senior Justice Department role. Additionally, Comey participated in a Senate investigation into the 1990s-era Whitewater scandal at the same time Justice Brett Kavanaugh worked on independent counsel Ken Starr’s investigation into the same issue.

Given the connections Scalia outlined in his recusal opinion, it’s safe to assume that most justices are familiar with Comey. He served as a high-ranking official in two presidential administrations and is recognized as one of the preeminent Republican lawyers in Washington, D.C. Comey embodies the same political fabric as the Republican justices.

It’s crucial for these justices to reflect on their similarities with Comey as they contemplate whether to rein in Trump’s escalating efforts to weaponize the Justice Department against political adversaries. Trump is not solely targeting Democrats; he is also pursuing individuals who are remarkably similar to the justices themselves. If they continue to act as sycophants for this administration without taking steps to restrain Trump, they could find themselves in the crosshairs next.

One of the bitter ironies in Trump’s prosecution of Comey is that without Comey, it is highly unlikely that Trump would have ascended to the presidency in the first place. When Hillary Clinton became Secretary of State in 2009, it was commonplace for high-ranking officials to conduct government business using personal email accounts—a practice followed by both of Clinton’s Republican predecessors. A senior official in Clinton’s State Department explained that such communication was often necessary for the secretary to respond swiftly to urgent matters.

However, Clinton’s choice to use a personal email account somehow morphed into the central issue of the 2016 election cycle, largely due to Comey’s actions. After the FBI concluded Clinton should not face prosecution for her email use, Comey, then FBI director, held a press conference labeling her actions as “extremely careless.” Just days before the 2016 election, he reignited the email controversy by sending a letter to Congress announcing the reopening of the investigation, a move that was quickly closed.

Such actions breached established Justice Department protocols. Former deputy attorneys general Jamie Gorelick and Larry Thompson noted that the DOJ operates under long-standing traditions that limit public disclosures about ongoing investigations—especially when there is a risk of influencing an election. Comey’s behavior created unfair innuendo that Clinton could not adequately counter.

The fallout from Comey’s actions was significant. Despite Clinton winning nearly 3 million more votes nationwide than Trump, she narrowly lost key battleground states like Wisconsin, Michigan, and Pennsylvania. The election was so close that Comey’s intervention likely tipped the balance. Had Comey adhered to the Justice Department’s safeguards against disparaging unindicted individuals and interfering with elections, Trump might have remained a struggling real estate developer.

One might assume that Trump would be eternally grateful to Comey for effectively paving his path to the presidency. Instead, Trump lost faith in Comey after the FBI began investigating potential ties between his 2016 campaign and the Russian government in 2017, leading to Comey’s dismissal from the FBI.

Since then, Comey has found himself on Trump’s enemies list. Recently, Trump inadvertently posted an order to Attorney General Pam Bondi on his social media platform, instructing her to target Comey, along with Senator Adam Schiff and New York Attorney General Letitia James.

Trump’s decision to pursue Comey underscores a troubling reality: he will turn against individuals who have previously aided him the moment he perceives any challenge to his authority. He is willing to leverage the full power of the U.S. government against those who displease him.

This serves as a stern reminder to the Republican justices, who may now reflect on their July 2024 ruling that granted Trump immunity from prosecution, even if he directs the Justice Department to target individuals “for an improper purpose.” The justices may share responsibility for the charges against Comey just as much as Comey bears for Trump’s presidency.

However, it is not too late for the Supreme Court to reconsider its stance. The Court currently faces several cases where Trump is seeking sweeping authority over U.S. fiscal and monetary policy. The Republican justices should not feel compelled to grant him this power, nor should they cooperate when Trump’s prosecutions of political adversaries reach their chamber.

Ultimately, if they choose to align with Trump, they will have no justification when he inevitably turns on them. The indictment of James Comey serves as a profound warning: even those Republicans who have made significant contributions to Trump’s ascent are not shielded from his vindictiveness.