In the ongoing discourse surrounding economic downturns, the definition of a recession has come under scrutiny. A prevailing narrative, notably pushed by certain commentators, claims that two consecutive quarters of negative GDP growth unequivocally signify a recession. This simplistic interpretation, however, overlooks the complexities of economic data and the nuanced understanding required to accurately assess the state of the economy.

EJ Antoni, in his piece titled “Biden’s Recession,” asserts a traditional view: “when the economy shrinks for two consecutive quarters, that’s a recession.” He argues that this has been a long-standing definition found in economics textbooks for over a century. However, this assertion fails to consider the evolving nature of economic metrics and the revisions that often occur long after initial reports are released.

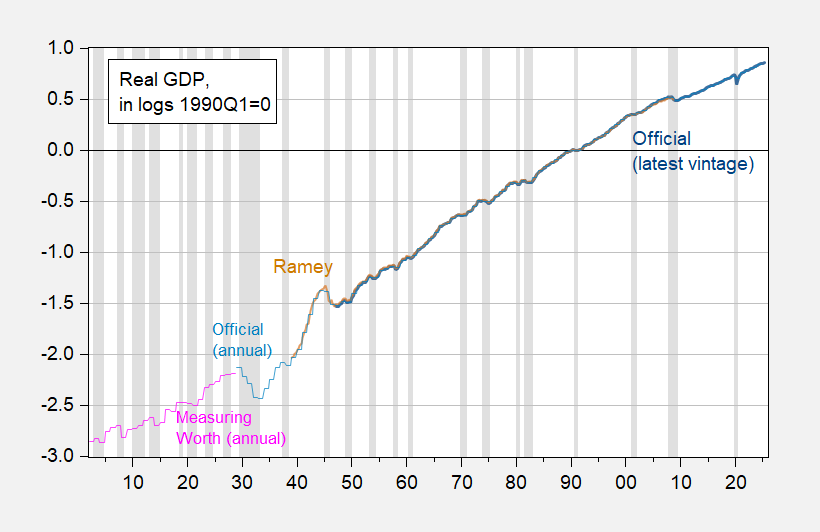

What many might find surprising is that the U.S. national accounts have been tracked since 1922, but the reliable quarterly data from the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) only dates back to 1947. Economists like myself, who have taught macroeconomics at institutions like UC Berkeley and UW Madison, understand that the definition of a recession is not as cut-and-dry as two quarters of negative growth. The National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER), which formally declares recessions, often waits to make its determinations because economic data is subject to revisions that can significantly alter our understanding of GDP trends.

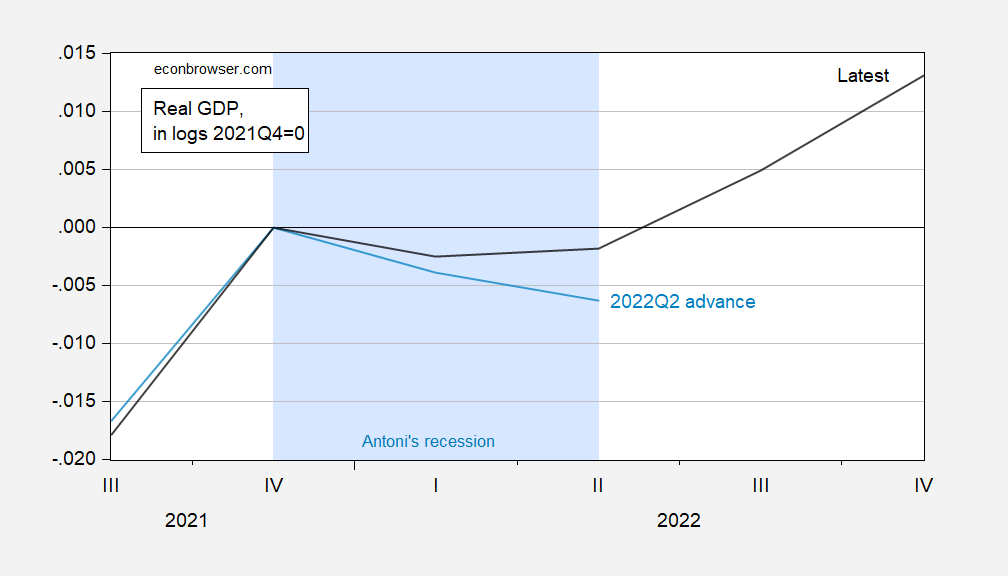

To illustrate this point, consider the GDP figures released for the second quarter of 2022. The initial estimates can change dramatically as new data comes in, which is why the NBER refrains from hastily labeling economic periods as recessions. Early estimates may show negative growth, but revisions can paint a different picture weeks or months later.

This is not a rare occurrence. The recession of 2001, for example, was only briefly characterized by two consecutive quarters of negative growth. Furthermore, the experience from 1947 demonstrates that there were two consecutive quarters of growth without an NBER designation of recession, challenging the notion that such a simplistic rule can capture the full economic reality.

Interestingly, Dr. Antoni himself has shifted his stance on this definition. Just four months ago, he suggested that the two-quarter criterion should not be applied in the context of potential negative growth in early 2025, indicating a recognition that public sentiment and economic conditions can complicate the matter of defining recessions.

In light of these considerations, it is crucial for the public and policymakers to engage with a more nuanced understanding of economic indicators. Relying solely on the two-quarter rule risks oversimplifying the complexities of economic cycles and could lead to misguided conclusions about the state of the economy.

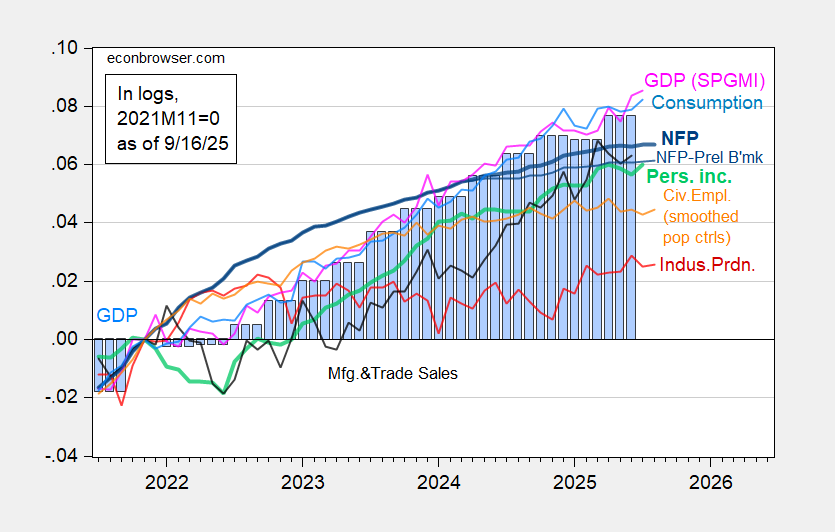

As we navigate through economic uncertainty, it is imperative that we rely on comprehensive data analysis rather than simplistic definitions. The health of the economy cannot be captured by a single metric; it requires a multifaceted approach that considers various indicators, including employment rates, consumer confidence, and broader economic trends. This perspective not only enriches our understanding of economic conditions but also equips us to make informed decisions that can better serve the needs of society as a whole.